Can you stop debt collectors from harassing and suing?

BY CHARLES PEKOW · AUGUST 9, 2014 ·

Collectors call again and again in the middle of dinner. They call the wrong person. They threaten. They take advantage of the latest technology to embarrass people. Often, they violate the law. Debt collectors will go to all sorts of legal and illegal means to intimidate people who owe or allegedly owe money. Collection has become a multi-billion dollar business, especially in the last few years as the slow economy had caused people to fall behind on payments.

About 30 million Americans were saddled with debt or alleged debt in collection in 2012, averaging about $1,500 according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

Realizing this, Congress created CFPB and granted it limited authority to write rules to govern part of the problem under the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010. Four years later, CFPB collected public comments on the problem over the winter. It plans to survey consumers this summer about their experience and knowledge of their rights.

“I used to be harassed by debt collection agency for a debt that was not my own. I used to have a different phone number. I had to change it because I kept on getting calls from a collection agency that were intended for the prior owner of the phone number. It did not matter how much I told them that they were calling the wrong number. I still got calls,” wrote Dylan Tate, a citizen responding to CFPB.

“What amazes me more than anything else is the impossibility of getting a wrongful debt removed from the record. I was a straw man in real estate and the person who stole my identity was arrested, tried and found guilty and sentenced and served time – YET – more than 15 years later I am still receiving calls from debt collectors for forged name documents and statements on my credit report for properties I never owned. How can this be stopped or cleared up?” wrote Gerald Elgert of Silver Spring, Md.

Though the slow economy exacerbated the problem, an improving one may not help. “Debt collection agencies will experience renewed demand,” as people regain ability to pay, Market research firm IBISWorld reported last November.

Medical debt – the largest source of unpaid bills. Medical bills and educational loans are eclipsing the traditional mortgages and auto loans as the fastest growing categories of debt in collection.

But CFPB’s new authority extends to only the largest companies – it estimates its proposed rules would cover about 175 firms. IBISWorld counted 9,599 firms in the business last fall.

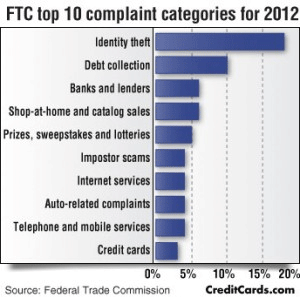

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has historically taken the lead role in the issue. The FTC “receives more complaints about debt collection than any other specific industry and these complaints have constituted around 25 percent of the total number of complaints received by the FTC over the past three years,” James Reilly Dolan, acting associate director of the FTC’s Division of Financial Practices said in July Senate testimony. The FTC got 199,721 collection complaints in 2012, up from 142,743 complaints in 2011 and 119,609 in 2009. Almost 40 percent of disputes about national credit reporting agencies concern collection. (FTC figures don’t include other complaints it gets that might include debt collection but it codes as identity theft or do-not-call grievances.)

So who is annoying the most people with repeated phone calls, threats, obscenity and other obnoxious tactics to collect debt? Largely major banks and collection agencies they hire.

In response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, the FTC provided a list of the companies getting the most complaints over a 28-month period. They had, by and large, already gotten into legal trouble but that didn’t stop them from continuing to bother people.

- NCO Financial Systems, Inc, a Horsham, PA collection agency (now Expert Global Solutions), with 6,223 complaints. In 2004, NCO paid the FTC $1.5 million, at the time a record debt collection fine. But last July, it broke its own record and paid the largest ever civil penalty in a debt collection case, $3.2 million. “It’s the one we get the most complaints about,” said consumer lawyer Craig Kimmel. Its “dialing system is otherworldly in its sophistication to keep calling people….They will keep calling until somebody pays and people will pay just to get rid of them.” Vaughn’s Summaries, a general reference website, called it “the worst debt collection agency.”

- Allied Interstate, Inc., part of iQor, a privately-owned conglomerate. Allied racked up 4,934 complaints covering everything from repeated phone calls to falsely representing alleged debts to calling at inappropriate hours. Allied paid $1.75 million in 2010 to the FTC to settle charges of telephone harassment – the second largest fine of its kind at the time. While Citibank, the nation’s third largest bank, doesn’t show up on the list of top violators, that doesn’t mean it’s not profiting from questionable tactics. Another division of parent company Citigroup owns a large stake in iQor. “I draw two conclusions,” stated Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) at a recent Senate hearing. “Citigroup and other banks think debt collection is a lucrative business. There’s a reputational risk to associating with those companies. Citigroup probably does not want their name on an aggressive means so they have iQor or Allied Interstate or something.”

- Portfolio Recovery Associates (PRA) with 4,481 cases, more than 1,000 of them charging callers with failing to identify themselves. The Norfolk, Va.-based company specializes in buying debt, especially of bankrupt people for a fraction of the value and trying to collect the entire sum. PRA is subject to at least five class action and multiple individual suits for alleged wrongdoing such as calling cell phones without permission. PRI denied to us that it breaks laws.

- Capital One Bank, an Allied client, with 3,054 accusations, including calling repeatedly and continuously, at inappropriate times, not sending written notices, refusing to verify debt, and profanity. Kimmel sued Capital One for harassing and demanding almost $287 million from a woman over a debt of less than $4,000.

- Deceptive trade practices and violating a 2009 order. The state charged that the bank continued to “mislead consumers with false promises” that they would not foreclose on homeowners while simultaneously foreclosing. Nevada also charged BofA with a litany of other misrepresentations including “falsely notifying consumers or credit reporting agencies that consumers are in default when they are not.” BofA paid penalties and agreed to change tactics.

- Midland Credit Management (MCM), a national debt buyer that use several names, including Encore Capital Group and Ascension Capital Group, with 1,778. MCM’s parent company reported to the Securities & Exchange Commission that it bought $8.9 billion in credit card debt during the first half of 2012 for about 4 cents on the dollar. The company specializes in suing debtors. MCM paid nearly $1 million in fines to Maryland in 2009 for alleged violation of state and federal laws, including operating without proper licensing. Though CFPB officially opened a complaint line in July about collectors, it got 750 such gripes in the first quarter of 2013, according to information received under FOIA. Consumers complained by far the most about Midland – 44 times, or six percent of the total.

- I.C. System at 1,767, mostly for calling “repeatedly or continuously.” The Minnesota Dept. of Commerce fined I.C. $65,000 for violating a variety of state laws, including failure to screen job applicants properly, hiring felons and not notifying the state that it dismissed at least 10 employees for using profanity. The U.S. Better Business Bureau received 807 complaints about I.C. in the last year.

- Similar name) at 1,644. The company went out of business after five state attorneys general sued it. NCS was acting on behalf of Hollywood Video, the movie rental service that went bankrupt in 2010. NCS was filing negative credit reports on consumers and threatening to sue them if video renters didn’t pay up. The problem stemmed from movie watchers who tried to return videos at stores that closed, said company founder Brett Evans. Though customers followed instructions to leave videos in a bin, their returns weren’t recorded and NCS tried to collect late fees.

- JP Morgan Chase, an NCO client, with 1,522. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) last September issued a Consent Cease and Desist order against Chase for multiple “unsafe and unsound practices” in its collection work, including filing misleading documents in court, not properly notarizing forms and not properly supervising its employees and contractors.

California’s attorney general sued the bank last year for allegedly routinely suing consumers for non-payment without following proper procedures. Unless otherwise noted, the companies either declined to address the charges or did not respond to inquiries. Mark Schiffman, spokesperson for ACA International, the largest collector trade group, said “they’ve made it pretty darn easy to complain in the first place. It’s not fair to say that the (FTC files) are a bellwether, that this is a horrible industry.”

The FTC got one of its largest settlements, $2.8 million, from West Asset Management last year. West didn’t show up on the above list as many people named their creditor, not the collection agency, when complaining. The Omaha, NB-based West agreed not to engage in tactics the FTC accused it of, including calling the same individuals multiple times a day, using “rude and abusive language” and disclosing information to third parties.

But West was making plenty of the calls that led to trouble for the banks. West said on its website that its clients include “seven of the top 10 credit card issuers, and other Fortune 500 companies.” The top five include four of the biggest sources of complaints: Chase, Capital One, Citigroup and BofA, according to Card Hub, an online search tool.

Only 15 lawsuits in nearly four years. It lacks the resources to handle every complaint so it focuses on the most serious abusers or cases that can establish a legal precedent. While CFPB is now taking complaints and can write rules, its small staff won’t be able to make more than another dent in the problem.

An FTC report on the issue said “based on the FTC’s experience, many consumers never file complaints with anyone other than the debt collector itself. Others complain only to the underlying creditor or to enforcement agencies other than the FTC. Some consumers may not be aware that the conduct they have experienced violates (the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, or FDCPA ). For these reasons, the total number of consumer complaints the FTC receives may understate the extent to which the practices of debt collectors violate the law.”

And much lies out of FTC jurisdiction. FDCPA, for instance, does not apply to banks, on the theory that banks are less likely to annoy their customers than an outside collector. If a bank harasses people, the victims can contact OCC or Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. But if a bank hires a collection agency, the consumers can go to the FTC. Judging by a look at the FTC complaint database, people are confused. “We do get a lot of complaints” about banks, said Tom Pahl, who served as assistant director of the FTC Bureau of Consumer Protection (BCP) before becoming CFPB’s managing regulatory counsel. William Lund, superintendent of the Maine Bureau of Consumer Credit Protection, said at a CFPB forum that people are so baffled that he gets many complaints from out of state.

What are consumers complaining about? The FTC log said that about half of debtors or alleged debtors simply complained of harassment. Thirty percent said they never even got a required written notice before calls came. A quarter said they got threats of civil or criminal action ranging from garnishing wages to seizing property, harming credit ratings and getting forced out of jobs. And 23 percent said the callers didn’t even identify themselves as debt collectors.

What are consumers complaining about? The FTC log said that about half of debtors or alleged debtors simply complained of harassment. Thirty percent said they never even got a required written notice before calls came. A quarter said they got threats of civil or criminal action ranging from garnishing wages to seizing property, harming credit ratings and getting forced out of jobs. And 23 percent said the callers didn’t even identify themselves as debt collectors.

About 16 percent complained of obscenity, eleven percent said collectors were violating the law by calling before 8 am or after 9 pm. and four percent cited threats of violence. Ten percent griped of efforts to collect unauthorized money (interest, late fees, and court costs). People also complained about everything from overstating debt, calling at work, continuing to call after getting a written notice not to, and not verifying debt when asked in writing or misrepresenting the law. (Many complaints alleged multiple violations.)

And 22 percent of the complaints regarded collectors bothering third parties, such as an alleged debtor’s family, friends, coworkers, employers and neighbors. By law, collectors may only contact other people to locate an alleged debtor. The FTC reported that collectors “have used misrepresenting as well as harassing and abusive tactics in their communications with third parties, or even have attempted to collect from the third party.”

And when you die, your debt doesn’t die with you and neither do collections. Collectors have often called relatives to ask if they’re the one who opens mail or paid for the funeral. If someone said “yes,” collectors have taken that as proof they’re the ones responsible and then asked about assets. So last year, the FTC decreed that collectors may inquire as to who has been designated the estate executor, and then only communicate with that person – and not try to collect debts before they locate the executor. Estates retain rights to contest claims.

Congress wrote FDCPA in 1977 – when collectors used rotary phones as the chief weapon to annoy people. So nothing in the law stops collectors from sending texts, emails and misleading Facebook friend requests to those they want to collect from. Collectors post messages on social network sites of friends and relatives. At a workshop on the issue, BCP Director David Vladeck said that though “using these communications media to collect debts isn’t by itself necessarily illegal, the potential for harassment or other abusive practices is apparent.”

Congress wrote FDCPA in 1977 – when collectors used rotary phones as the chief weapon to annoy people. So nothing in the law stops collectors from sending texts, emails and misleading Facebook friend requests to those they want to collect from. Collectors post messages on social network sites of friends and relatives. At a workshop on the issue, BCP Director David Vladeck said that though “using these communications media to collect debts isn’t by itself necessarily illegal, the potential for harassment or other abusive practices is apparent.”

The law gives the FTC no authority to write rules. The law prohibiting contact before 8 am or after 9 pm was intended to apply to telephones and it’s not clear whether it applies to after-hours email. And FDCPA includes no criminal penalties.

Two years ago, an FTC report stated “neither litigation nor arbitration currently provides adequate protection for consumers. The system for resolving disputes about consumer debt is broken.” Arbitration efforts flopped. Three years ago, the Minnesota Attorney General sued the National Arbitration Forum, citing fraud, deceptive trade practices and false advertising – the forum didn’t tell people of its financial ties to the industry. The forum settled and stopped arbitrating.

Consumers also get confused because of the growing debt buying business. Companies specialize in buying debts usually for between five and ten cents on the dollar, then trying to collect the whole shebang. (The nation’s 19 largest banks sell about $37 billion a year in credit card debt, according to OCC.) So people hear from a company they’ve never heard of claiming they owe money. Almost no one engaged in this practice in 1977 so it’s not clear how FDCPA affects debt buyers. People can pay their original creditor after it sold the debt and think they’ve settled the matter, only to face continued collection efforts from the buyer.

OCC said it is working on guidance and “has raised its expectations for banks” in this regard. “Selling debt to third party debt collectors carries particular compliance, reputational, and operational risks,” OCC said in a statement given in July to Brown adding “it is evident these risks are gaining increasing prominence.” Brown said that “OCC has historically been more friendly to banks than to consumers.”

Kim Phan, a lawyer for debt buyer trade association DBA International, said the organization is working on guidance for the industry.

Collectors do more than call and harass. They sue. The New Economy Project (NEP), a New York community advocacy center, recently released a report stating “debt collection lawsuits — particularly those filed by debt buyers — wreak havoc across New York State, depriving hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers of due process and subjecting them to collection of debts that in all likelihood could never be legally proven.”

In 2011, collectors – mostly buyers – filed 195,105 lawsuits against New Yorkers. Almost two-thirds of the time, plaintiffs win default judgments but seldom win on the merits when cases go to trial, NEP said. “A lot of the debt that we see that’s charge-off by banks is debts that they’ve sold off for pennies on the dollar with very little documentation so the banks aren’t held accountable for that debt and the collectors who are trying to collect…are doing so with very limited information and sometimes don’t have sufficient proof and therefore rely on robosigning and other abusive tactics,” declared Alexis Iwanisziw, NEP research and policy analyst, speaking at a July CFPB forum.

Congress has ignored legislation introduced in recent years to modernize the law. In previous years, senators Charles Schumer (D-NY), Al Franken (D-MN) and Carl Levin (D-MI) conducted hearings and introduced bills but failed to move them. They dropped the issue in the current Congress. Their offices did not respond to inquiries.

Brown, however, examined the issue at a July hearing of his Senate Banking, Housing & Urban Affairs Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Protection. Brown said in an interview “I don’t know about a legislative solution” and that recent events gave him “hope we may be able to do something (but) we won’t reopen Dodd-Frank in a major way.”

OCC: More Third-Party Risk Guidance

Regulator Outlines Steps to Mitigate Merchant Processing Risks

By Tracy Kitten, August 26, 2014.

In keeping pace with increasing industry pressures to address third-party risks associated with payments breaches, yet another banking regulator has come out with revised guidance about what banking institutions should do to address risks associated with merchant processing.

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s leading agency, has released an updated version of its Merchant Processing booklet, highlighting emerging concerns about high-risk merchants and the need for more due diligence when it comes to the management and risk assessment of third-party service providers.

The payments breach at retail giant Target Corp., which was the result of an attack against a vendor, as well as a breach at payments processor Fidelity National Information Services have pushed banking regulators to reiterate why banking institutions are responsible for mitigating third-party vulnerabilities.

Updated Booklet

The OCC booklet, which was first published in December 2001, provides updated guidance for examiners and banks about how they assess and manage risks associated with card-related payments processing. Additionally, the OCC has added supervision guidance for federal savings associations, which it says should now be treated like any other third party.

Also featured is updated guidance about technology service providers, Payment Card Industry data security standards for merchants and processors, and Bank Secrecy Act compliance programs and appropriate policies for anti-money-laundering controls.

Al Pascual, director of fraud and security at consultancy Javelin Strategy & Research, says the guidance is extremely relevant in the current security environment.

“This just further reinforces the fact that managing the risks associated with third-party providers has become an absolute necessity,” he says. “The doors have been shut and the windows closed, so that in the event that a financial institution fails in their responsibility to vet these counterparties, then they have nowhere to go. There is no excuse.”

Last month, the FDIC, another FFIEC agency, issued a statement to clarify third-party risks associated with payments processors and high-risk merchants (see FDIC Clarifies Third-Party Payments Risks).

And Aug. 7, the PCI Security Standards Council came out with new guidance to help merchants and banking institutions mitigate the ongoing risks posed by third parties that process and, in some cases, inadvertently store payment card data.

Increasing Third-Party Risks

More card breaches are being traced back to the breach of a third party, banking regulators and industry advisory boards say.

In early August, Troy Leach, chief technology officer of the PCI Council, in speaking about recently released version 3.0 of the PCI Data Security Standard, said recent research has shown that 65 percent of all data breaches involve a third party and 45 percent involved retailers.

“Many of the recommendations you will see here from the [PCI] council highlight the same types of requirements you are starting to see at the federal level, regarding what service-level requirements may be needed to ensure security with third parties,” Leach says.

In April, Controller of the Currency Thomas Curry said ensuring due diligence and ongoing risk assessments of all third parties must be a part of every banking institution’s vendor management program. He also noted banking institutions have to be responsible for monitoring and ensuring the ongoing security of the vendors with which they work, even if those vendors are subject to regulatory oversight (see OCC’s Curry: Third-Party Risks Growing).

Late last year, the OCC became the first major U.S. banking regulator to issue updated guidance about third-party risks, noting eight specific areas where banks needed to make improvements to their vendor management programs related to third parties. Among those recommendations were guidelines related to how banking institutions should terminate relationships with third parties if certain security criteria are not met.

Honing in on Payments

Now the OCC is focusing attention on card-payments risks and the role third parties often play in the exposure of card data when it’s being processed.

Paul Reymann, a compliance and risk-management professional of bank advisory firm McGovern Smith Advisors, says in the wake of the Target breach, banking regulators are clearly giving third-party risks more attention.

Reymann notes that banking institutions have about 122 pieces of regulation or guidance related to third-party risk management with which they are expected to comply or adhere. While that seems overwhelming, he points out that there is quite a bit of overlap among those regulations and guidelines. The Graham, Leach, Bliley Act, enacted way back in 1999, requires all banking institutions to protect the consumer information from “foreseeable threats in security and data integrity,” he explains.

What’s happening now, Reymann adds, is that banking regulators, such as the OCC, are merely reiterating why and how mitigating third-party risks must be a priority to ensure the integrity and security of financial and payments data.

“Kudos to the banking regulators for putting guidance out about how to manage third-party risks and asking the banking institutions to take a lead role in doing that,” Reymann says. “We’re expected to implement controls to identify and mitigate that kind of risk. What we need to think about going forward is, ‘How do we get these non-regulated entities that are working with highly regulated financial institutions to be more proactive? How do we get the third parties themselves to be exam-ready, especially the critical vendors?”

Payments Risks

In its updated guidance, the OCC points out that banks are required to have GLBA compliance programs, as well as policies, procedures and processes in place to safeguard confidential customer information.

“The potential exists for legal liability related to customer privacy breaches,” the guidance states. “The bank’s GLBA risks when dealing with a third-party processor that possesses confidential customer information are the same as the risks when the bank possesses the information.”

In fact, any card data that is stored or transmitted is at risk, OCC points out, and banks have to take the lead to ensure that data is protected.

Debt Collection Attorney Oversight Called Into Question – Literally

Stephanie Levy August 7, 2014 Inside ARM

Should the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issue guidance about what it considers appropriate attorney oversight when filing debt collection lawsuits? According to a recent insideARM.com home page poll, readers are split on the issue.

According to the poll, 64 percent of poll participants generally believe that the CFPB should provide guidance on attorney oversight. But in taking a closer look at the numbers, 36 percent of readers think the CFPB should issue the guidance because not enough exists, while 27 percent of poll participants want there to be official Bureau guidance because they want to avoid any potential lawsuits. 34 percent of readers disagree, saying the practice of law is best left in the hands of the judiciary system, not regulators.

“The precedent for meaningful review has been set,” one reader commented. “It’s just a wonder it took so long.”

In July, the CFPB filed a lawsuit against Frederick J. Hanna & Associates, a debt collection law firm, alleging that the firm was a “lawsuit mill” that churned out debt collection actions and violated the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act. These alleged practices make it seem as though collection attorneys weren’t really reviewing cases before sending them to court. However, some debt industry experts warned that the CFPB’s involvement with the issue was a violation of the separation of powers.

The impact of CFPB oversight on all players in the debt industry is going to be a hot topic at ARM-U, insideARM.com’s first ever training and networking seminar covering the latest compliance and operations issues. Expert attorneys Ronald Canter, Kim Phan and Anita Tolani will outline what the regulatory future looks like for debt collectors – and how agencies can prepare for the future right now.

Debt Buyer News

OCC Releases Rules for Banks Selling Consumer Debt

AUG 5, 2014 11:18am ET Collections and Credit Risk

New guidelines for the sale of consumer debt, issued Monday by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, detail the steps banks must take before selling charged-off consumer loans. Notably, the OCC plans to make banks responsible for performing due diligence on debt buyers before a sale.

Federal and state regulators increasingly have targeted debt buyers that violate consumer protection laws, but banks generally have not been held responsible for these companies’ conduct.

The OCC’s debt-sales guidance expands on and formalizes the best-practices guidance on debt sales that the OCC released last July. While the best practices were recommendations geared to large banks, the new guidance applies to all institutions regulated by the OCC, regardless of size.

The OCC expects banks to analyze the risks of consumer debt sales and provide accurate information to debt buyers. The guidelines also cover what types of consumer debt can be sold and specify the account information that banks must include when selling debt.

The guidelines are a result of the OCC’s three-year review of large banks’ debt collections and sales, which state attorneys general and whistleblowers have claimed are riddled with problems.

“Before a bank enters into a contract with a debt buyer, the debt buyer should be able to demonstrate that it maintains tight control over its network of debt buyers and that it conducts activities in a manner that will not harm the bank’s reputation,” the guidelines say. “Banks contemplating entering into a relationship with debt buyers should first assess the debt buyer’s record of compliance with consumer protection laws and regulations.”

JPMorgan Chase entered into a consent order last year for allegedly selling accounts that were incorrect or missing crucial information and accounts that had been paid or discharged in bankruptcy, as well as floating laws designed to protect military servicemembers. JPM neither confirmed nor denied these claims.

The OCC’s investigation largely confirmed that there are serious problems with banks’ internal controls over their consumer debt sales. It identified examples when banks “transferred customer files [that] lack information as basic as account numbers or customer payment histories” and when “banks gave debt buyers access to customer files so they could assess credit quality before the debt sale,” in violation of privacy laws. It also found that banks sell debt without first investigating the buyers.

The OCC guidelines, in response to the identified problems, require that banks provide debt buyers with signed customer contracts, account numbers, copies of the last 12 account statements and the date, source and amount of the last payment.

It forbids banks from selling certain categories of debt that “fail to meet the basic requirements to be an ongoing legal debt” and to refrain from selling debt that poses compliance and legal risk, such as debt covered by the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act.

Segment in Focus: Debt Buyers – A Rapid Consolidation Anticipated

Mike Ginsberg August 26, 2014

For many ARM professionals, adjusting to a world of intense government oversight, mounting client pressures, increased operating costs, and an economy slow to recover has been challenging to say the least. For US debt buyers in particular, functioning in today’s environment has been extremely difficult. Amidst momentous market changes, many debt buyers, sellers, investors and vendors alike are asking the same question: Will a major consolidation among US debt buyers result?

My short answer is yes. Consolidation has already started and the pace will pick up steam in the next 12-24 month. Before I explain why I believe a major consolidation of debt buyers will result, let’s look back at what took place in recent years that set the table for whether a consolidation among debt buyers is inevitable.

The US debt buying segment of the ARM industry really began to form when the RTC (later the FDIC) sold non-performing loans created from the Savings and Loan Crisis of the 1980s and 1990s. That segment of the market picked up steam in the mid-1990s, and for the next decade leading up to the Great Recession, as major banks consistently sold non-performing, non-secured loans, resulting in the formation of two industry associations and hundreds of large and midsize buyers aggressively expanding their operations to handle the substantial flow of new business available in the market.

While most ARM companies also serviced other market segments, and many provided additional service offerings, the debt purchase market really feasted on portfolios made available for purchase from a handful of large credit card issuers. Financing was also readily available at attractive rates to finance debt purchases creating the perfect storm for US debt buyers. The rewards of significant profits were apparent and debt buyers were not visibly concerned with the possibility that one day the music might stop playing and the business flowing into their operations might slow down.

In the late 1990s, I remember being asked if the US ARM industry, consisting mostly of third party collection agencies at that time, would consolidate. At that time, my answer was no way in spite of the fact that large agencies were merging at an astounding pace because of the influence of private equity capital and NCO Group’s aggressive acquisition strategy. Consider that during the decade from 1996 to 2006, nine of the ten largest US collection agencies went through at least one M&A transaction. In fact, GC Services was the only ARM company in the top 10 during that period that did not transact. The pace of mergers and acquisitions during that time period was staggering and anyone without industry knowledge might draw the same conclusion that the industry was in the midst of a major consolidation. However, that was not the case for three fundamental reasons:

- New ARM companies were being formed at an astounding rate as barriers-to-entry did not exist at that time.

- Credit grantor clients would not tolerate having a handful of vendors servicing their needs instead of a competitive marketplace. Grantors drove competition among their vendors, not consolidation.

- Government regulators were not severely impacting the performance of collection operations at that time.

Let’s fast forward to 2012. It was around 2012 that the CFPB initiated their first round of large bank audits and change started setting in. Over the next two years, some banks stopped selling debt altogether while others dramatically reduced the amount of portfolios available for purchase. Impact was felt immediately among large debt buyers who purchased direct and later on from secondary buyers. If that wasn’t enough, the CFPB started auditing non-bank financial institutions in 2013, which included debt buyers, and the staggering cost of compliance started settling in. Feasting quickly became famine and debt buyers focused on the banking sector were forced to make quick decisions to survive.

Today, debt buyers are marching to a new drummer. The large issuers and other credit grantors that sell portfolios are no longer calling the shots themselves. Government regulators including the CFPB and the FTC are driving market conditions today, demanding fewer vendors and more operational oversight than ever before.

Now that I laid out the playing field, I will list my reasons why I strongly believe that a major consolidation among US debt buyers will result:

- Large credit card issuers have dramatically reduced loan originations and delinquencies dropped significantly as consumers paid off debt incurred prior to 2008, resulting in significantly less debt available for debt buyers to purchase directly. Debt buyers will gobble up each other to feed their operations as evidenced by some recent moves made by Encore Capital.

- The secondary debt selling market, a pillar of success for most debt buyers, has been completely decimated, dramatically impacting the profitability of debt buyers that relied on resale to recoup costs of buying large portfolios through secondary sales. The removal of the secondary debt selling market has also severely crippled the small (zip code) and mid-size debt buyers, forcing them to look at other market segments for survival or selling their portfolios to larger debt buyers and shuttering operations.

- The significant and consistently escalating cost of operating a debt buying company has created a true barrier of entry for new participants to form, resulting in fewer players overall.

- Overbearing compliance requirements have made buying portfolios nearly impossible for most debt buyers who lack the stability and transparency demanded by the few issuers selling portfolios today. The few credit card issuers who are selling have dramatically cut the number of debt buyers they sell to in order to comply.

- Capital is not readily available to most debt buyers like it was leading up to the Great Recession.

- Emerging markets and other asset classes have not created a sustainable flow of new accounts to replace the shortfall in the market from large issuers not issuing new credit at levels realized prior to the Great Recession.